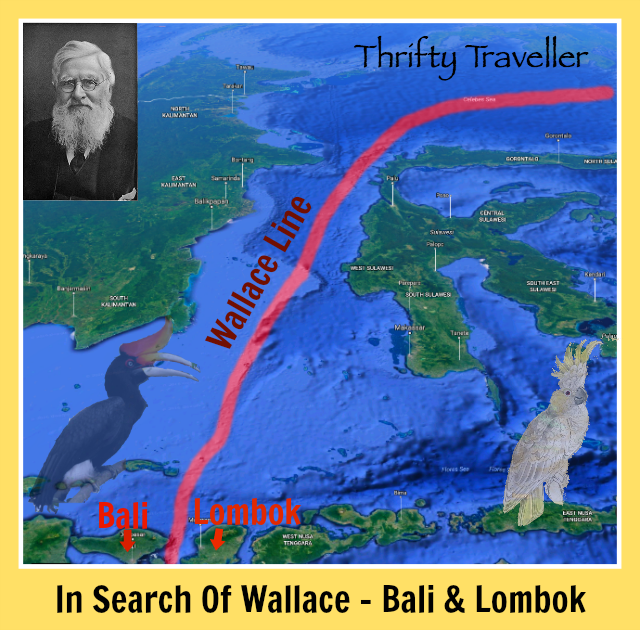

Last week, after a break of several months, I resumed my efforts to retrace Alfred Russel Wallace’s footsteps in the Malay Archipelago, this time by visiting the area around Makassar in southern Sulawesi. (I’ll use the old spellings of Macassar and Celebes for the purpose of this post.)

Wallace reached Macassar in August 1856 on board the schooner Alma, brimming with optimism. He wrote:

I left Lombock on the 30th of August, and reached Macassar in three days. It was with great satisfaction that I stepped on a shore which I had been vainly trying to reach since February, and where I expected to meet with so much that was new and interesting.

His first impressions of the town were positive:

Macassar was the first Dutch town I had visited, and I found it prettier and cleaner than any I had yet seen in the East. The Dutch have some admirable local regulations. All European houses must be kept well white-washed, and every person must, at four in the afternoon, water the road in front of his house. The streets are kept clear of refuse, and covered drains carry away all impurities into large open sewers, into which the tide is admitted at high-water and allowed to flow out when it has ebbed, carrying all the sewage with it into the sea.

Today Macassar is a city of around 1.5 million but in Wallace’s time it was a lot smaller:

The town consists chiefly of one long narrow street along the seaside, devoted to business, and principally occupied by the Dutch and Chinese merchants’ offices and warehouses, and the native shops or bazaars. This extends northwards for more than a mile, gradually merging into native houses often of a most miserable description, but made to have a neat appearance by being all built up exactly to the straight line of the street, and being generally backed by fruit trees. Parallel to this street run two short ones which form the old Dutch town, and are enclosed by gates. These consist of private houses, and at their southern end is the fort, the church, and a road at right angles to the beach, containing the houses of the Governor and of the principal officials. Beyond the fort, again along the beach, is another long street of native huts and many country-houses of the tradesmen and merchants.

The fort, called Fort Rotterdam, still survives and is one of the town’s top tourist attractions. This, together with the church, the adjacent vicarage, and a handful of other colonial-era buildings are all that remain of the old Dutch town.

There was no hotel in Macassar so Wallace stayed initially at the Dutch club, known as the Sociëteit De Harmonie, located close to the fort. The building still stands, though much altered in appearance, with a sign showing it has been used as an art centre.

Wallace’s initial optimism soon turned to disappointment and by September he was writing to a friend:

At length I am in Celebes! I have been here about three weeks, and as yet have not done much, except explored the nakedness of the land,–and it is indeed naked,–I have never seen a more uninteresting country than the neighbourhood of Macassar: for miles around there is nothing but flat land, which, for half the year, is covered with water, and the other half is an expanse of baked mud (its present state), with scarcely an apology for vegetation…. Insects, in fact, in all this district there are absolutely none.

Wallace wanted to widen his search:

Before I could move to any more promising district it was necessary to obtain permission from the Rajah of Goa, whose territories approach to within two miles of the town of Macassar. My friend Mr. Mesman kindly lent me a horse, and accompanied me on my visit to the Rajah, with whom he was great friends. We found his Majesty seated out of doors, watching the erection of a new house.

The Gowa Regency was abolished by the Dutch after Wallace’s visit but the area where Wallace and the Rajah may have met (Benteng Somba Opu) has been turned into a museum, with the remains of demolished fortress walls on display together with a number of replica traditional buildings from around Celebes.

Wallace didn’t think much of the local coffee:

Some wine was then brought us, and afterwards some detestable coffee and wretched sweetmeats, for it is a fact that I have never tasted good coffee where people grow it themselves.

In the interior of southern Celebes the villagers were unused to seeing foreigners:

Not a single person in the village could speak more than a few words of Malay, and hardly any of the people appeared to have seen a European before. One most disagreeable result of this was that I excited terror alike in man and beast. Wherever I went, dogs barked, children screamed, women ran away, and men stared as though I were some strange and terrible cannibal or monster. …… If I came suddenly upon a well where women were drawing water or children bathing, a sudden flight was the certain result; which things occurring day after day, were very unpleasant to a person who does not like to be disliked, and who had never been accustomed to be treated as an ogre.

Wallace had much better luck in searching for species at Maros, which he visited during a second trip to Celebes from July – November 1857:

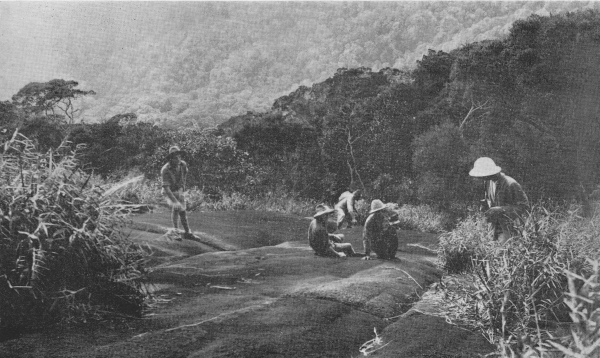

After much inquiry I determined to visit the district of Maros, about thirty miles north of Macassar. …. Passing over an elevated tract forming the shoulder of one of the hills, a picturesque scene lay before us. We looked down into a little valley almost entirely surrounded by mountains, rising abruptly in huge precipices, and forming a succession of knolls and peaks aid domes of the most varied and fantastic shapes.

This area is now a national park called Bantimurung.

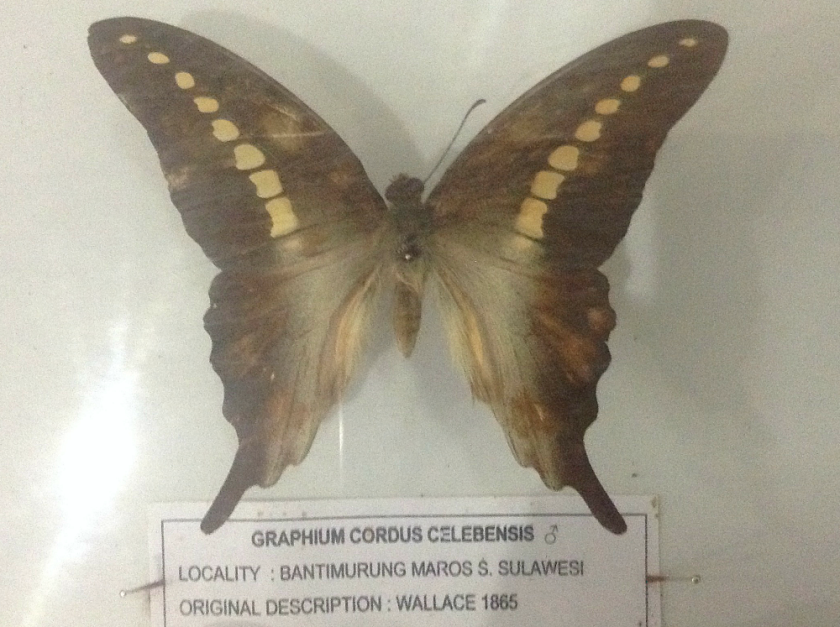

The rare and beautiful Butterflies of Celebes were the chief object of my search, and I found many species altogether new to me, but they were generally so active and shy as to render their capture a matter of great difficulty.

They are not easy to photograph either, as this blurry picture shows. I must invest in a good camera and super-dooper lens one of these days.

In these rocky forests dwell some of the finest butterflies in the world. Three species of Ornithoptera, measuring seven or eight inches across the wings, and beautifully marked with spots or masses of satiny yellow on a black ground, wheel through the thickets with a strong sailing flight. About the damp places are swarms of the beautiful blue-banded Papilios, miletus and telephus, the superb golden green P. macedon, and the rare little swallow-tail Papilio rhesus, of all of which, though very active, I succeeded in capturing fine series of specimens. I have rarely enjoyed myself more than during my residence here.

There is a rather tatty butterfly museum inside the national park containing some fine butterfly and moth specimens caught locally and elsewhere in Indonesia. Wallace’s name appears under a number of the specimens for having provided the original descriptions.

Wallace counted 250 species of butterfly at Bantimurung and dubbed the area the Kingdom of Butterflies. When a local university professor carried out a census in 2005 , only 125 species were identified. Given the number of stalls outside the national park selling butterflies I suppose we should be grateful there are any species left at all.

Wallace is still remembered at Bantimurung. He even gets a prominent mention on the National Park’s official website.