In 1980 my former employer, a well known Hong Kong bank, transferred me from Oman to Hong Kong. The day I landed at Kai Tak airport, a driver met me and deposited me at my new home, a low-rise apartment in an old block in Happy Valley, overlooking the racecourse.

Waiting for me in the flat was Ah Tai who was to be my amah for the next two years. Although I paid her salary, (HK$ 1200 per month if I recall correctly), she was informally engaged by the bank to look after the apartment. In theory, I need not have employed her, but after a 30 second interview she decided I was a suitable employer and she agreed to stay on.

She was a live-in helper and had a tiny room off the back of the kitchen. The kitchen was also her territory and I would seldom venture in there. She kept the flat spotless and the ageing furniture was still in remarkable condition considering that a string of bachelors had lived in the flat over the years.

Ah Tai did the washing and ironing. I don’t even know if we had a washing machine but my shirts were always hanging back in the cupboard clean and crisply ironed a few hours after taking them off.

She ensured I was never late for work despite my many evenings as a young bachelor carousing in the bars of Hong Kong. One breakfast I had a dreadful hangover and was struggling to finish the eggs and bacon that she laid on the table every morning. She tut-tutted “Master, why you got red eyes?”

She spoke a kind of basic Chinglish. Male employers were always called Master and if there was a female boss she would be Missie. I took Cantonese lessons for a while and though she was amused by my pathetic pronunciation she, in common with most HK Chinese, did not really encourage me to learn her language. The less we gweilos knew what was going on, the better! The British officers in the Royal Hong Kong Police were the only gweilos I knew who really could really get to grips with the language.

Ah Tai could cook Western and Chinese dishes but was better at the latter. Before leaving for work she would ask if I was coming home for dinner. If yes, she would ask for a small sum to buy groceries. She would take the bus down to Wanchai food market and haggle with the vendors for fish, meat, vegetables and fruit.

I was supposed to pay for her food but she was super-frugal and cost next to nothing. If she cooked me fish, she would eat the fish heads with a bowl of rice and a few vegetables. When I ate an orange, she would keep the peel and dry it on the kitchen window ledge for use as a snack or home remedy. She practiced reduce, reuse and recycle long before it became fashionable.

She would give me a ticking-off if I didn’t come home for dinner after saying I would. And it was no use me trying to phone her. I tried it once:

Me: Hello Ah Tai

Her: Wai?

Me: Ah Tai

Her: Wai?

Me: It’s me, master.

Her: Master not here! (slams down phone).

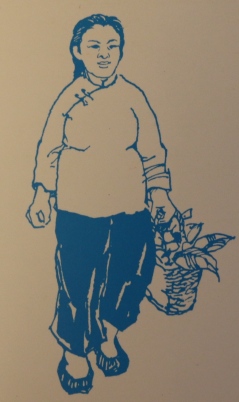

We never discussed her background or personal life. She spent her leisure time in the kitchen listening to her transistor radio. On Saturdays she would sometimes go out and return on Sunday evening, exchanging her usual white top and black silk trousers for a more colourful outfit of the same style. Perhaps she went to see a relative or meet up with other amahs to swap funny stories about their bosses or to exchange investment tips. Chinese amahs were famously good at saving every cent they earned and, investing wisely in shares and property, some became quite wealthy.

Hong Kong’s black and white amahs (referring to the colour of their attire) were a superior class of domestic helper with roots in Shunde County of Guangdong Province. Being hard working and reliable they were in great demand in Hong Kong among expatriates and wealthy Chinese. The wealthiest families employed a number of amahs, one for cooking, one for cleaning, one for looking after children and so on. Ah Tai was a yat-keok-tak (one leg kick) meaning that she did everything. Black & white amahs had good prospects for life-long employment, leading to financial independence with no need to rely on a drunken, cheating, gambling, wife-beating husband for support. As a result they never married and took a vow of celibacy.

By 1980, Hong Kong’s amahs were a disappearing breed as younger Chinese girls were unwilling to take up this career, with better paid opportunities available in factories and offices. They were replaced by domestic helpers from the Philippines (and later Indonesia and elsewhere) who were less expensive and, not speaking Chinese, less able to interfere and find out all the family secrets.

I don’t know what became of Ah Tai after I was posted back to the Middle East. The above photo was taken 35 years ago. She would be quite old by now but with her healthy diet and ascetic lifestyle, who knows, she could still be going strong. Wherever she may be, I thank her for looking after me.

These are the photos kindly forwarded by Judy Wilkinson to accompany her comment below: