Virtual Holiday in the Spice Islands

I need a holiday but that’s not going to happen while this global lockdown is in place. So I though I would take a virtual or pretend holiday and write a blog post about it.

Where to? I decided on Banda Neira in the Malaku Islands (Moluccas) of Indonesia, about midway between Sulawesi and Papua. It’s a place I’ve been meaning to go to for some time. Thanks to the internet and having already visited many Indonesian islands I can have a pretty good idea of what to expect so I’m writing this blog as if I have actually been there.

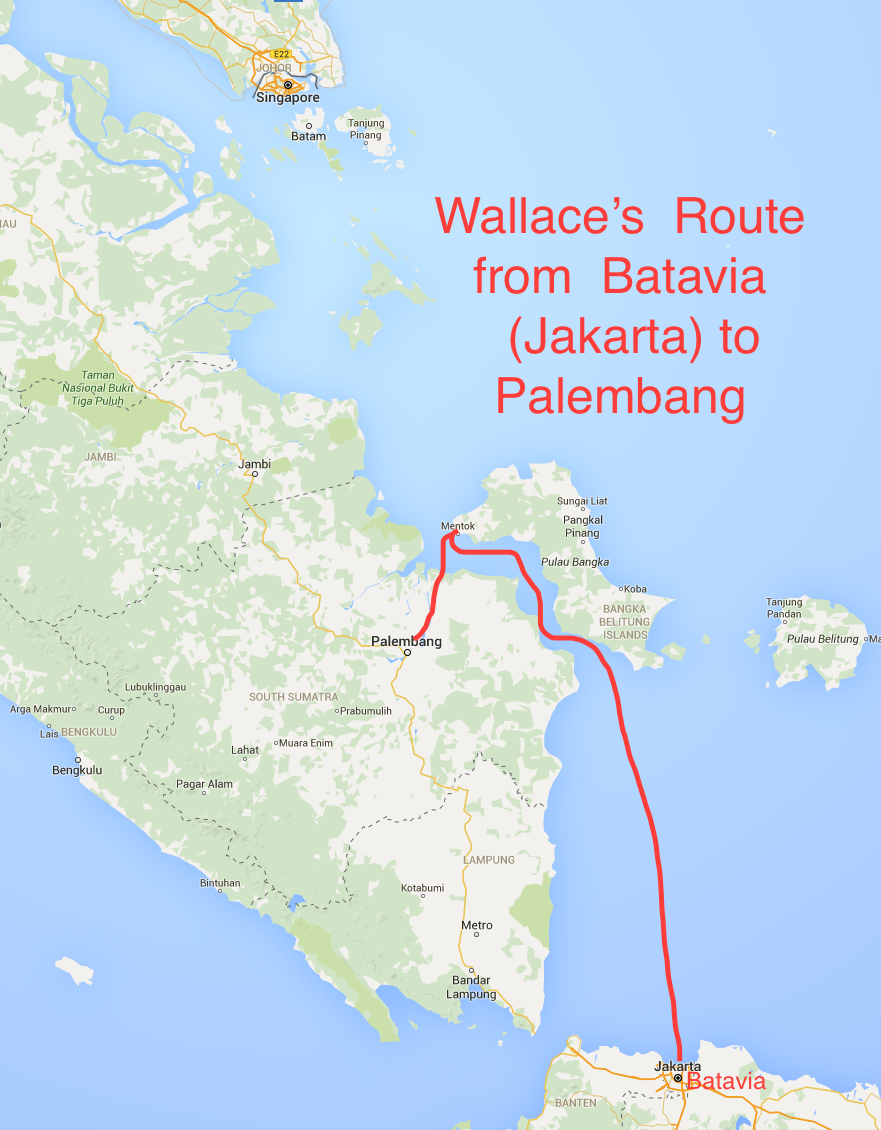

My Journey to Banda

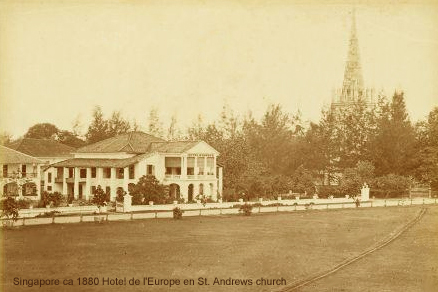

I decided to take a ferry to reach Banda. There is an airstrip with scheduled flights from Ambon, Jakarta,Surabaya and Makassar, but the runway looks rather short and some of the smaller airlines in Indonesia do not have the best safety record and flights are always being cancelled or delayed so I thought a ferry might be a better option. A fast ferry leaves Ambon for Banda Neira twice a week at this time of year when the sea is calm but only if there are enough passengers. It normally takes 6 hours but this time it was cancelled. So I was left with the only other option which was to take a slow ferry Government-owned ferry called the Pelni which stops at Banda about twice a month from Ambon. The journey time was 12 hours but can take 19 hours depending on sea conditions. Basic meals were included in the IDR 100k ticket price (£5) consisting of rice, vegetables and tempeh.

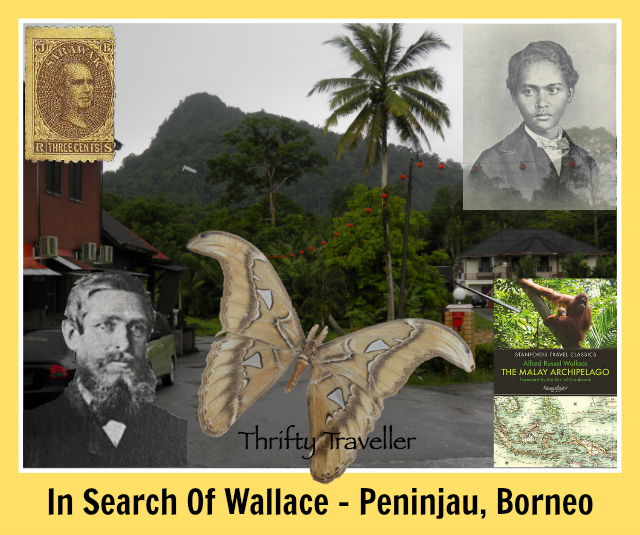

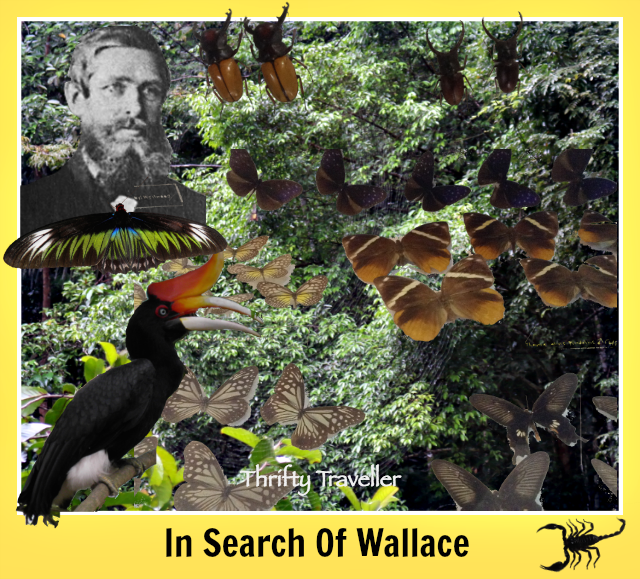

Conditions on board were better in Alfred Russel Wallace‘s time when he travelled to Banda in 1857 by Dutch mail steamer. His meals were as follows:

6 a.m. tea or coffee

8 a.m. light breakfast of tea, eggs, sardines etc

10 a.m. aperitifs on deck; Madeira, gin and bitters

11 a.m. substantial brunch

3 p.m. tea and coffee

5 p.m. aperitifs again

6.30 p.m. a good dinner with beer and claret

8 p.m. tea and coffee

free-flowing beer and soda water between meals.

My arduous journey was rewarded when I clapped eyes on Banda which comprises three beautiful islands enclosing a tranquil harbour with crystal clear water overlooked by a classical shaped volcano and jungle clad hills.

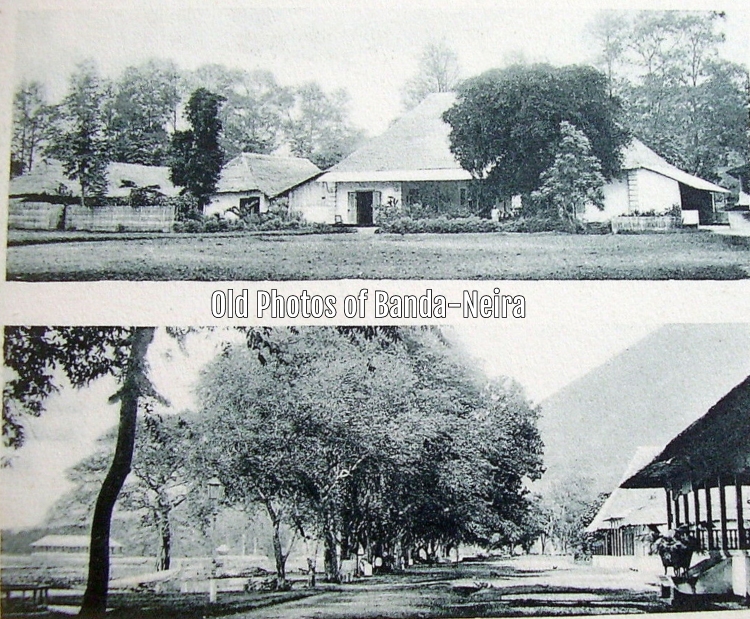

During the Dutch colonial era these islands were the chief nutmeg garden in the world at a time when nutmeg was more highly prized than gold. The spice trade brought prosperity to the Dutch merchants living here who were so rich they didn’t know what to do with their money so they built fancy marble-clad houses with wide verandas. There’s not much evidence of wealth these days and the few Dutch houses which still survive are very much faded. Nutmeg is still cultivated here and you can catch a whiff of nutmeg, cinnamon and pepper in the air, along with the ever-present fragrance of Indonesia’s clove cigarettes.

My Accommodation

I decided to stay at the Mutiara Guesthouse in the centre of town for its cosy feel, its convenient location and its reasonable reviews. Breakfast was particularly good, banana pancakes, scrambled eggs, fried eggs or omelette, tasty coffee and fresh tropical fruits.

Better than in Somerset Maugham’s day. This is his description of breakfast in the 1932 novel The Narrow Corner which was set in Banda Neira (he called it Kanda-Meria):

“Breakfast in the little hotels in the Dutch East Indies is served at a very early hour. It never varies. Papaia, oeufs sur le plat, cold meat and Edam cheese. However punctually you appear, the eggs are cold … the coffee is an essence to which you add Nestlé’s Swiss Milk … the toast is dry, sodden and burnt. Such was the breakfast served in the dining room of the hotel at Kanda and hurriedly eaten by silent Dutchmen, who had their offices to go to.“

DAY 1. Sightseeing – Fort Belgica

After checking in the hotel and freshening up I set out to explore the sights of Banda. My first stop was Fort Belgica, a grey stone castle built on a low hill immediately behind the guesthouse. It was one of several forts built by the Dutch on the Banda islands to protect their grip on the world’s nutmeg trade. It replaced an earlier 16th century Portuguese fort.

The Dutch began their construction in 1611 and it was expanded, strengthened and rebuilt several times since with the current pentagonal design completed in 1673. It survived several earthquakes and volcanic eruptions but surrendered to the British without firing a shot in 1796 and again in 1810, having been handed back to the Dutch in 1803. The fort was comprehensively restored in 1991 and is now a tourist destination.

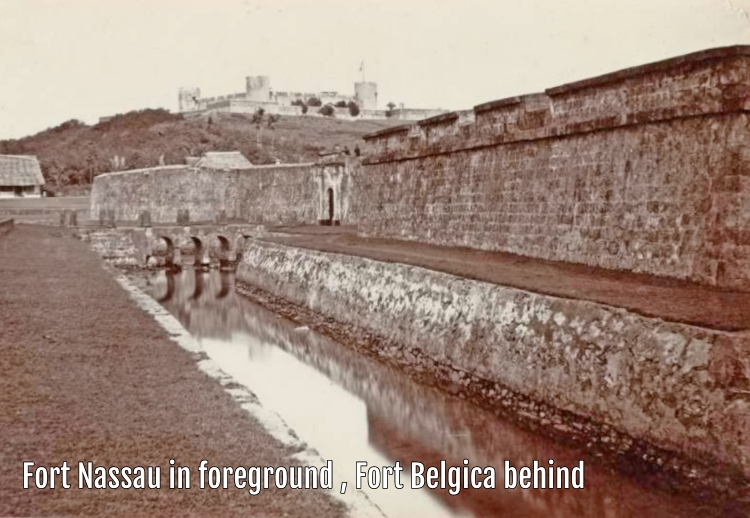

Fort Nassau

Next I took the short walk to Fort Nassau which was an earlier fort completed in 1609. It was rectangular shaped with four stone bastions and had a moat. It is now mostly dilapidated and overgrown. As you can see from this old photo it was overlooked by Fort Belgica.

Nutmeg Café

Feeling thirsty and hungry by now I took a break at the Nutmeg Café and filled up with some nasi goreng and nutmeg jam pancake washed down with iced nutmeg juice. To tell you the truth I’m not mad about the taste of nutmeg but the juice was refreshing.

Parigi Rante

This is an old well and monument listing the names of 40 Banda fighters and chiefs who were among the many killed in 1621 during Dutch Admiral Simon Janszoon Coen’s conquest of the islands. The names of 20th century Indonesian freedom fighters are also commemorated here.

Rumah Pengasingan Bung Hatta

This small, simple house is where Bung Hatta was exiled from 1936-42 as a political prisoner by the Dutch colonial authorities. Bung Hatta is the affectionate nickname for Mohammad Hatta (1902-1980) who is an Indonesian national hero and was one of the leaders in its struggle for independence from Dutch rule. During his exile he ran school classes on the terrace of the house which is now a cultural heritage monument and museum containing a few items of furniture and possessions of Bung Hatta.

Istana Mini

Just 100 metres away from Bung Hatta’s house is the Istana Mini, an elegant colonial mansion built in 1820 as residence for the Dutch Contrôleur or inspector/governor. The grounds of the residence face the sea and lead out to a small pier where the Contrôleur and his guests would have disembarked. The main building consists of six rooms, all sparsely furnished, in fact, empty. Off to one side is a statue of King Willem III (1817-1890).

Gereja Tua Banda

Heading back to the town centre somewhat I passed Gereja Tua Banda, an old church built in 1873. Inside, the floors are paved with a number of tombstones, mostly of Dutch but some British, many of which predate the church. Many of the tombstones are large in size and elaborately carved, similar to the Dutch graves found inside the ruined church on St. Paul’s Hill in Melaka.

Rumah Budaya Banda Neira

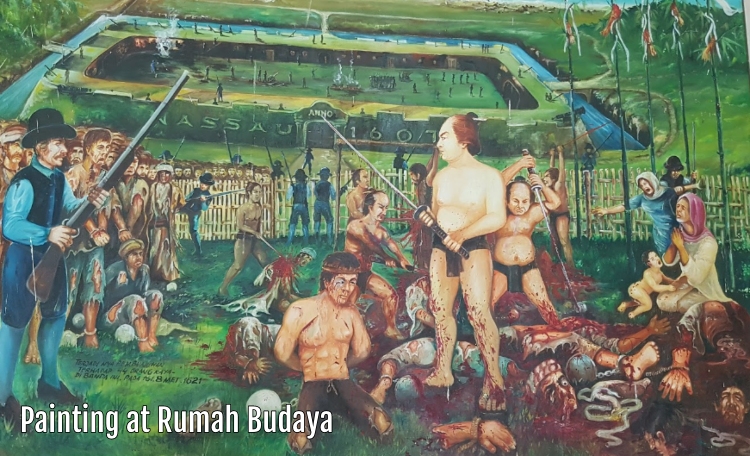

Just along the street, Rumah Budaya Banda Neira is a small local history museum. There are a few interesting exhibits here including a gory painting of Dutch atrocities against the Banda islanders using Japanese mercenaries to do their dirty work. Certainly the Dutch used harsh measures in order to gain monopoly control of the nutmeg trade and some scholars estimate that 90 percent of the local population was killed, enslaved or deported during the campaign.

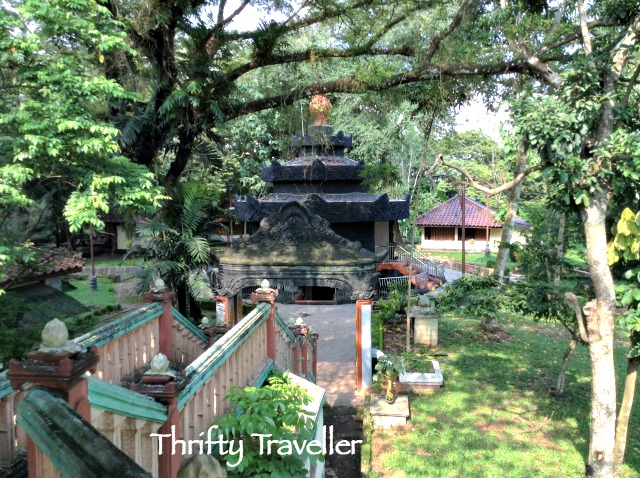

San Tien Kong Chinese Temple

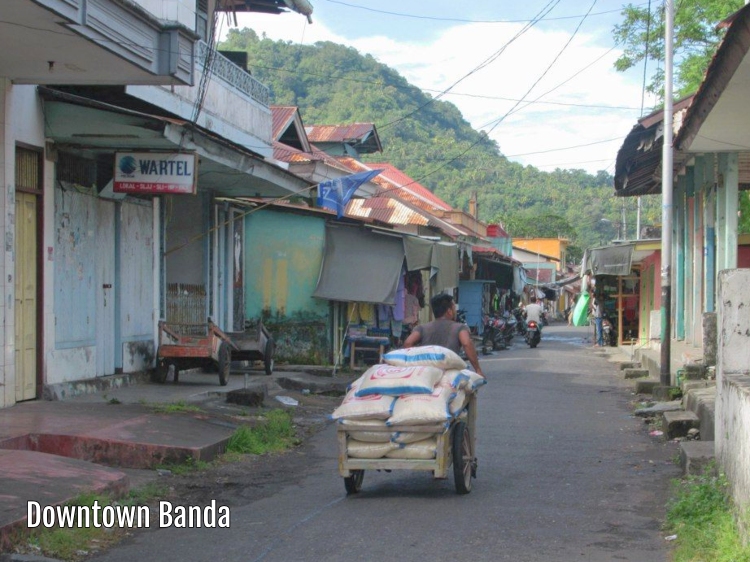

To round off the day I wandered through the main commercial streets, such as they are. There was not a lot going on. Most of the shops were shuttered for the day, or forever, and they were few in number anyway. The entire population of the Banda islands is probably less than 20,000 so I didn’t expect huge shopping malls. The Chinese population, who always add vibrancy to south east Asian towns and were once numerous on Banda, have largely moved on elsewhere and only a handful of families remain. The Chinese temple was locked up and looked abandoned. Christians too have mostly migrated to other islands following sectarian conflicts in the late 1990s.

I had a quick look at the fish market, all closed for the day but still reeking with dried fish being left out in the open on the waterfront. Then I watched the boats at Banda Neira Harbour overlooked by Gunung Api which is my destination for tomorrow.

DAY 2. Hiking Gunung Api

Early the next day I arranged through my hotel for a boatman to ferry me over the short stretch of water from Banda Neira market jetty to the trailhead of Gunung Api, the perfect cone-shaped volcano whose name means ‘fire mountain’.

The volcano is 640 metres high and is still active with the last major eruption being in 1988, spewing a river of lava into the sea, luckily not in the direction of Banda Neira town. This day there was just a wisp of smoke rising from the summit, merging with low clouds.

The hike started with a sweaty but pleasant climb through spice gardens, bamboo glades and jungle before emerging onto a steep, bare slope covered in loose volcanic scree. This part was exhausting but from around 500 metres above sea level the path became firmer underfoot. With no shade, I was glad of my long sleeves, hat, sunblock and plenty of water.

The view from the crater rim was great, especially looking back over Banda Neira. I could see the airport where the runway looked worryingly short from this height.

I descended without incident and managed to find a boatman to take me back. The whole hike took me about 4 hours up and down. Younger, fitter people can do it in 3 hours.

Peter Piper Picked A Peck Of Pickled Peppers

Since I still had nearly half a day I asked the boatman to drop me at the third of the Banda islands, Banda Besar. As the name suggests it is the largest of the three but thinly populated and mostly covered in jungle.

Above the village of Lonthoir, reached by a 313 step staircase, is Kelly Plantation where I could see nutmeg trees up close.

In the early 1600s nutmeg was more valuable than gold. A small sackful could fetch enough money in London to last a lifetime. Why was nutmeg so valuable? During the black death it was believed to be able to ward off bubonic plague, perhaps because fleas dislike the smell of nutmeg. (Would it work for coronavirus? Probably not). It was also an efficient preservative enabling meat to be kept for longer periods without going off.

As mentioned the Dutch tried every trick in the book to hang on to their nutmeg monopoly, even going so far as to produce deliberately misleading maps to hide the islands’ location. But eventually nutmeg plants were smuggled out and successfully transplanted elsewhere. One man who is often credited with doing this was Pierre Poivre, an 18th century French missionary, trader and adventurer who went on to to become Governor of Mauritius where he established botanical gardens for propagating his smuggled nutmeg, cloves and other spices. This man, whose name literally translates as Peter Pepper, is often thought to be the origin of the Peter Piper tongue-twister.

Benteng Hollandia

Close to Kelly Plantation is another old Dutch fort, Benteng Hollandia.

This fort was built of coral stone in 1624 to guard the sea approaches to Neira and to monitor the activities of the nutmeg and mace trade in the area.

The fort was devastated by an earthquake in 1743. It was later repaired but neglected again from 1811 onwards and today is in ruins. Its hill top position means that it has excellent views towards Gunung Api.

DAY 3. Snorkelling

My hotel manager recommended the best spots for snorkelling in the sparking, clear waters around Banda. The area where lava flowed from Gunung Api’s 1988 eruption is particularly rich in coral and diverse marine life. The lava initially killed off the coral but it has since recovered and regenerated into a beautiful underwater landscape.

I spent a pleasant day relaxing on the beach and snorkelling above the coral. Remembering the fortune-teller’s prophecy in which I am to be eaten by a shark (see here) I didn’t go looking for reef sharks.

That completes my virtual holiday. Having spent some time researching this post I think I now know the Banda Islands quite well and there’s no need for me to visit in real life. That’s saved me quite a lot of money. Thrifty Traveller!