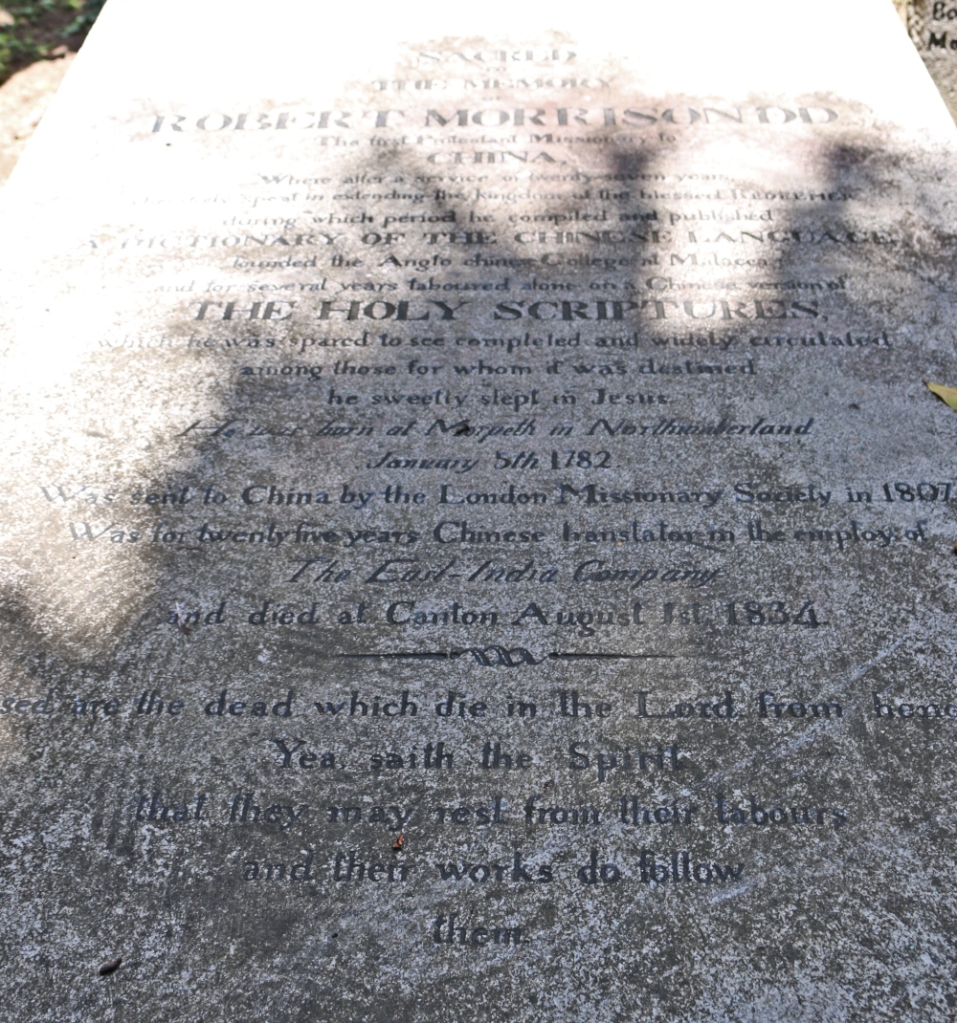

In a corner of the tranquil Protestant Cemetery in Macau lies the grave of Robert Morrison, recognised as the first Protestant missionary to China. He translated the Bible into Chinese and compiled and published an Chinese/English dictionary.

I visited the graveyard in 2015 and took this photo of his tombstone. The lighting was poor but you might just be able to make out that he was born in Morpeth in Northumberland on January 5th 1782.

Since I am familiar with Northumberland, Macau and Malacca (all places connected to Morrison) I thought I would see if I could find out more about this devout and steadfast man.

He is generally thought to have been born on a street called Bullers Green on the outskirts of Morpeth (though some say he was born in the tiny hamlet of Wingates, about 11 miles from Morpeth and moved to Bullers Green in infancy). The house at Bullers Green no longer stands but this is the location:

The inscription above the archway reads Victoria Jubilee Year. This house replaced the one in which Robert Morrison D.D. was born. (DD means doctor of divinity).

When he was three the family moved to Newcastle-upon-Tyne where his father established himself as a last and boot maker in Groat Market which might have looked like this at the time. The street has far less character today.

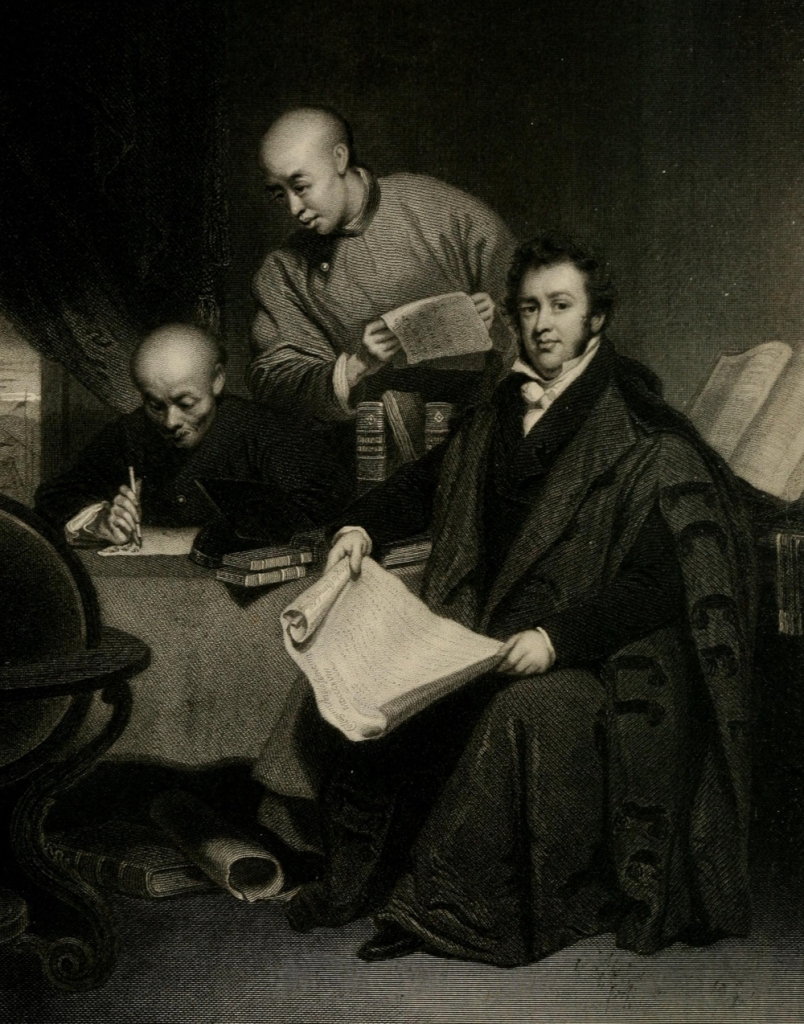

Robert, the youngest of eight children was a serious and hard working boy and had a strict religious upbringing by his Presbyterian parents. At age 14 he left school and trained as an apprentice in his father’s cobbler business. As a teenager he went slightly off the rails, falling into bad company and, like many a Newcastle lad, was prone to excessive drinking on occasion. However, after having the fear of eternal damnation drummed into him by his pastor he reformed his ways, and eventually passed his examinations as a clergyman and applied to the London Missionary Society to serve abroad. He learned some Chinese in London and was selected to start a mission to China. Although his wish was convert ‘poor perishing heathens’ the objectives set were more practical; to compile a Chinese dictionary and translate the New Testament into Chinese. Any conversions he achieved along the way would be a bonus.

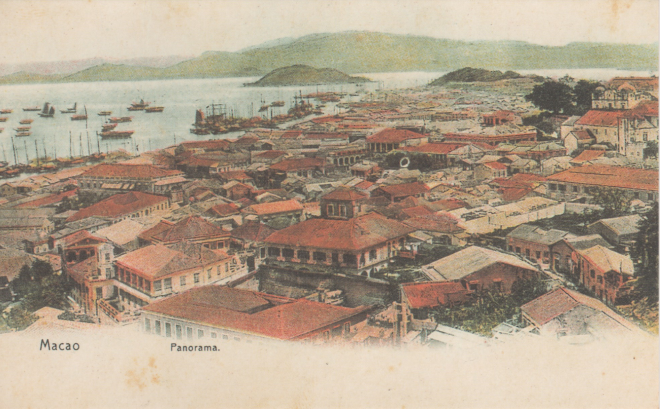

It was no easy task and he was not made welcome. For a start Christian missionaries were banned in China, on pain of death for the preacher and the converts. That is why he only converted ten Chinese over a period of 27 years. Secondly Chinese were forbidden to teach their language to foreigners and anyone who has tried studying Chinese knows that it is one of the hardest languages in the world to master. Thirdly, the Roman Catholic priests in Macau did not want Protestant clergymen in their territory and pressed the Portuguese authorities to expel him. The East India Company, which controlled most of the British trade in Macau and Canton, did not allow missionaries to travel on their ships so Morrison was forced to arrive on an American ship disguised as an American. And the British and other foreign traders did not welcome criticism from a Bible-bashing Brit since they were nearly all involved, directly or indirectly, in the opium trade. Morrison described many of his countrymen as riff-raff, unjust, covetous, avaricious, lying, drunken and debauched. They in return regarded him as irritating, narrow-minded, scornful and completely humourless.

Somewhat ostracised he was left in lonely isolation he was able to devote himself to his dictionary and, only when this had been published and he had become fluent in Chinese, did he become useful to the East India Company who employed him as a translator. He married Mary Morton in 1809, the daughter of an East India Company surgeon, and they kept each other company in their seclusion. They had two surviving children but she died of cholera in 1821 and, since Morrison would not have his wife buried in a Catholic cemetery, the Protestant cemetery was established in Macau. He later remarried and had a further five children.

Morrison died in Canton on 1 August 1834 and his body was brought to Macau and buried next to his first wife and child. By the time of his death the entire foreign community in Canton and Macau had come to admire his character, even if they didn’t much like him. A fellow missionary, an American Sinologist called Samuel Wells Williams, summed Morrison up as ‘not by nature calculated to win and interest the skeptical or the fastidious, for he had no sprightliness or pleasantry, no versatility or wide acquaintance with letters, and was respected rather than loved by those who cared little for the things nearest his heart’.

Morrison’s name is also associated with Malacca (in Malaysia). Another missionary, William Milne, was sent out to assist Morrison, arriving in Macau in 1813 but he was not permitted to stay. After some time in Canton, he moved on to Malacca where, under Morrison’s guidance, he established a school called the Anglo-Chinese College in 1818. After Hong Kong became a British territory the school relocated there in 1843 under the name Ying Wa College. It is still going today. Milne died in Malacca and he is commemorated in Christ Church, Malacca.

Marques was not particularly happy with his situation in Hong Kong and was interested to migrate. Indeed over the 120 or so years since his time, many of the Portuguese/Macanese population of Hong Kong moved on to new lives in places like Canada, Australia and Portugal.

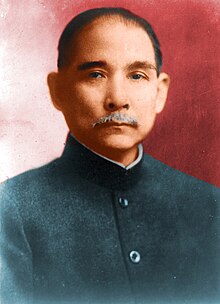

Marques was not particularly happy with his situation in Hong Kong and was interested to migrate. Indeed over the 120 or so years since his time, many of the Portuguese/Macanese population of Hong Kong moved on to new lives in places like Canada, Australia and Portugal. During Rizal’s short residence in Hong Kong another Asian national hero and revolutionary, Sun Yat-sen, the future first President of China, was also in Hong Kong as a student at the Hong Kong College of Medicine. They do not appear to have met despite the fact that Marques was one of Sun Yat-sen’s lecturers.

During Rizal’s short residence in Hong Kong another Asian national hero and revolutionary, Sun Yat-sen, the future first President of China, was also in Hong Kong as a student at the Hong Kong College of Medicine. They do not appear to have met despite the fact that Marques was one of Sun Yat-sen’s lecturers.